The last month or so has been taken over by various global conflicts that seem to repeat some of the most vexing foreign policy challenges of the 1980s: the conflict in the Middle East, particularly the Gaza region, and Russian relations with its East European neighbors. Those interested in international relations find their attentions divided between these two regions due to two sadly violent events taking place simultaneously: the military conflict between Israel and Gaza, and the shooting down of a Malaysian Airlines passenger plane over Ukraine, where about 300 people died. This brings forth the question of how do international relations and international security stakeholders react to long lasting conflicts that feature the messy combination of ethnic and national disputes over limited geographical boundaries. This entry will focus on the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, and try to look at how the debate over the development of a history textbook for Russian elementary schools can illuminate the reasons behind the violent evolution of Putinism in the border between Russia and Ukraine. The connection between the debate over a history book and the debate over the land in Eastern Ukraine may not seem evident at first. However, the way the debate over the textbook evolved points helped to illuminate Putin’s view regarding Russia’s historical condition has facilitated the escalation of tensions in the Ukrainian territory.

This story, as most stories about the current state of Russia, starts with the Soviet period and how it developed school curricula. The United States for the most part leaves textbook choice selection to the discretion of the individual school districts. Under the Soviet Union, Russia developed a nationally centralized curriculum. The 1988 literature readers for fourth and fifth grade mirror each other in their structure. They progress in a roughly chronological order. The first section features traditional folk tales. The second section contains adaptations of folk tales written by Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin. The third section contains samples of nineteenth century literature. Works by Soviet writers focusing on the evolution of the new Soviet society round out the last section. Each section includes an essay focusing on a particular aspect of the section’s reading, be it plot, character development, or a comparison of prosaic and poetic language. The readers present a unified heroic narrative of the evolution of Russia. It also includes stories that feature young children as heroes, be it as Young Pioneers of as witnesses of heroic military struggle. It sends a message to the young ten to twelve year old audience that they are part of the heroic mission of Russia, particularly Russia as the leading republic within the Soviet Union.

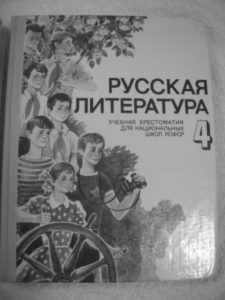

Fourth Grade Russian Literature Reader for the Russian Federation, academic year 1988

Fifth Grade Russian Literature Reader for the Russian Federation, Year 1988. Notice the positioning of the young boy, presumably the fifth grader, and his encounter with the heroic Soviet soldier from what could be interpreted to be the heroic first half of the twentieth century.

Russia has maintained the policy of using centrally produced textbooks in the post-Soviet era. What has proved particularly curious is the high profile the central government has given to the development of national textbooks, particularly the development of a new Russian history school. January 16, 2014 featured a meeting of the committee charged with developing the new history textbook. Some of the professionals who participated come from fields traditionally related to curriculum development: the minister for education and science, various members of the Russian Duma’s education committees, history teachers from the K-12 realm, the head of the history department at Moscow State University, as well as faculty members from several other Russian institutions of higher learning. Some of the participants, however, prove a curious addition to what one would expect to be a pedagogical task force. The head editor for the Russian History television channel and the Archimandrite of the Sretensky Male Monastery formed part of the textbook development committee. While some argument could be made for the possible interest in the History channel’s view of how media can influence the development of history curriculum, the presence of the archimandrite begs the question of how the Russian government views issues regarding the separation of church and state when it comes to curriculum development.

Outside of the issues of the curious composition of the curriculum committee, there is also the fact that Vladimir Putin actively charged them with the design of the new textbook. The transcript of the meeting on January 16 shows Putin defending what he sees as a need for unified treatment of Russian history within the national curriculum.

Концепция, которая доработана и уже принята, насколько я понимаю, должна лечь в основу и целой линейки учебников и методических пособий.

Сразу в этой связи хотел бы сказать, что единые подходы к преподаванию истории совсем не означают казённое, официозное, идеологизированное единомыслие. Речь совершенно о другом: о единой логике преподавания истории, о понимании неразрывности и взаимосвязи всех этапов развития нашего государства и нашей государственности, о том, что самые драматические, неоднозначные события – это неотъемлемая часть нашего прошлого. И при всей разности оценок, мнений мы должны относиться к ним с уважением, потому что это жизнь нашего народа, это жизнь наших предков, а отечественная история – основа нашей национальной идентичности, культурно-исторического кода.[1]

The Kremlin provided an official English translation of this statement that gives a general idea of what Putin stated, but which also makes some unfortunate word choices in trying to convey some interesting Russian concepts.

The concept, which has been finalised and adopted, as far as I know, should form the basis for an entire set of textbooks and study guides.

I would like to begin by saying that coordinating our approach to the study of national history does not mean formal, official, ideology-driven single-mindedness. We are talking about something different: a single logic in teaching history, an understanding of the inseparability and interconnectedness between all stages in the development of our state and statehood, the fact that the most dramatic and ambiguous periods are an inseparable part of our past. There is a wide range of assessments and views on these issues and we should respect them, because this concerns the life of our nation and of our predecessors, and our history is the basis of our national identity, our cultural and historic code.[2]

I would like to focus on the first sentence of the second paragraph of the quote. Here, Putin defends the need for a unified presentation of Russian history while trying to address the fear of Soviet styled censorship of uncomfortable historic periods, such as the Stalinist period from 1928 to 1952. «Сразу в этой связи хотел бы сказать, что единые подходы к преподаванию истории совсем не означают казённое, официозное, идеологизированное единомыслие.» The Kremlin provided the following translation: “I would like to begin by saying that coordinating our approach to the study of national history does not mean formal, official, ideology-driven single-mindedness.” While the Russian original really does sound as mind-numbingly bogged down in jargon as the English translation, there is a significant problem with how they translate one phrase: казённое, официозное, идеологизированное единомыслие. Kазённое means bureaucratic, related to the state – governmental. Oфициозное means something not official but that conveys the government point of view. Идеологизированное means to idealize, in the sense of imagining something as better than what it is. Eдиномыслие refers to someone who thinks the same as some other person, but not in the sense that unanimity conveys that idea. Thus, the phrase should read closer to: “First off, I would like to say in relation to this that a common approach to the teaching of history does not mean governmentally driven idealized concurrence.”

Putin looks to standardize the presentation of history while uplifting those areas he finds most positive, and without over-emphasizing negative events. While he does not mention it explicitly, it seems like he is looking to figure out a way to minimize the negative side of the Soviet period, particularly the Stalinist purges. He also sees this history curriculum as a possible way to unify a country that saw itself in such disarray during the last decade of the twentieth century.

So what, pray tell, does this have to do with Putin’s reaction to events in the Ukraine? First, it shows a consistency to how Putin views the nature and role of the Russian state in a post-Soviet world. Ever since his inaugural address in December 31, 1999, Putin has emphasized again and again that he sees a strong, centralized state structure as an integral part of the Russian nation. He also has pushed for a vision of Russian history as one uninterrupted unbroken process, instead of several periods broken by radical change. [3]

If one starts with that understanding of Putin’s world view, one can understand why he would see it as necessary to assert Russia’s influence in regions that have historically been considered to fall under Russia’s sphere of influence. Ukraine occupies a particular spot in this equation due to the flowing nature of the Russian borders during the nineteenth and twentieth century. The issue of the Crimean peninsula highlights this complex set of issues. Nikita Khrushchev transferred Crimea to Ukraine in 1954 through a declaration by the Politburo of less than a page in length. This did not matter from a security standpoint during the Soviet period, since the Ukraine belonged within the confines of the Soviet Union. After the fall of the Soviet Union, however, it provided a point of tension due to its high percentage of ethnic Russians and the nature of its transfer to Ukraine. One of the main challenges Putin has faced since 2000 is managing the tricky calculus of ethnic and civic tensions that have emerged in the borders of post-Soviet Russia. The United States press has generally paid attention to the tensions in the Central Asian regions of Russia, where Muslim national groups have presented a challenge to the Russia’s centralized federal structure. Its position on the Eastern region of Russia – read: its geographical location in the non-European regions of Russia – have meant that European and North American governments have not reacted in a particularly strong way to Russian governmental and military activity. However, Putin’s expansion beyond Russia’s Western European rational-legal post-Soviet borders have agitated European and American governments that for the most part viewed the issues of post-Soviet borders settled in 1991-1992.

Putin’s view of Russia’s legitimate sphere of influence in the Western region of Russia and Eastern Europe complicates important aspects of relations with an increasingly interconnected European region. Most significant is the growing dependence of Europe on Russian gas, and the Soviet legacy of Eastern European reliance on gas from Russia. Simply stated: if Eastern Europe sees its pipeline to Russia cut off then they will find themselves facing a really cold winter. Phrases that have become clichés such as “energy independence” and “renewable energy sources” take on a much more real dimension. Russia’s increasing level of trade with Europe also proves challenging. Trade, however, still has some Soviet legacies, so the percentage of Russian trade with Europe is still much larger than the percentage of European trade with Europe. Read: if trade levels go down, Russia gets more affected than Europe.

Finally, this highlights American foreign policy’s continuing difficulty in dealing with the other “N” word: “Nationalism.” Nationalism, in Putin’s view, is important in creating a strong Russian state. It, however, causes great problems when conflicting claims to one territory occur, particularly when the claims are framed in terms of “Slavic” or “Russian” essentialist terms. Put in really explicit terms: does Ukraine really have a claim to Ukrainian right to exist if it is nothing but a descendant of an original Russian ethnic territory? Ukraine’s attempts at closer ties to Western Europe – read: independent of great Mother and Father Russia – becomes a real threat to Russian national sovereignty within its ideally constructed territories. Ethnicity, nationality, and statehood then become the volatile mess that we witnessed in Central Asia before and in Ukraine today.

[1] Встреча с авторами концепции нового учебника истории. 16 января 2014 года, 15:45, Москва, Кремль. http://www.kremlin.ru/news/20071

[2]“Meeting with designers of a new concept for a school textbook on Russian history.” http://eng.kremlin.ru/news/6536

[3] Vladimir Putin. “The Modern Russia: Economic and Social Problems.” Vital Speeches of the Day. February 1, 2000. pp. 231-236 and Meeting of Council for Interethnic Relations http://www.eng.kremlin.ru/transcripts/5017.