One of the problems with teaching is that you cannot quite get away from nagging problems so you can focus on research and writing. In this case, the three main problems have been related to late implementation of fall semester assignments. So… Problem #1: Since I was assigned my courses late, and the textbook manager went on a well-deserved (and I mean that seriously, without irony) vacation, I still have to order my textbooks, so I have not been able to finish my syllabi for next semester. Problem #2: I was assigned my courses late, so I have yet to finish my syllabi. Problem #3: I am still dealing with next semester, when next semester is supposed to be already planned and done. This gets in the way of drawing full benefit of enjoying the full effect of summer defamiliarization – остранение. As I mentioned in a previous blog, there is a need to disconnect from the familiar to recognize the full complexity of the structures of the familiar. In the academic setting, what a lot of professionals do not realize is that a good academic tends to fulfill three full time jobs. The first, and usually most visible, is teaching and promoting knowledge among students. The second is defined as service, where the academic serves on committees that help administer the university – usually in the form of committees or special programming on campus. The third, and usually most complicated, falls under the heading of “research.” Research often includes outside sources of funding for their work. Research usually culminates in various forms of publications, where the academic shares their knowledge with the public at large. This includes publishing articles, books, traveling off-site to conduct research, and presenting at conferences. If you keep track, that tends to amount to two and half to three times the workload of a mainstream nine to five job.

The biggest challenge tends to be fulfilling the research part of this equation. Research, by its very nature, tends to be a solitary endeavor, demanding monastic practices bordering at times on the obsessive. In the humanities, this tends to require substantial travel to libraries, archives, and historical sites to gather all necessary materials. Summer, in short, is not an unexpected vacation bonus time, but rather a frantic race to finish research before mid-July and August, when most archives shut down for the summer, and then finishing anything from a twenty page article to a two to three hundred page book manuscript before orientation starts, in some cases as early as mid-August. Untethering from campus and the cacophony of demands found there proves vitally important for what most of us consider the most important part of our jobs: the dissemination of knowledge.

This year I have taken my traditional trip to the Midwest. I am also engaging in a trip to a Dominican retreat center in McKenzie Bridge, Oregon. The idea is to contemplate – yes, in that deep and religious manner. Many students fail to understand how self-consciously our moral beliefs tend to help shape our research. The small community of gulag scholars, for instance, are frantically trying to collect interviews with surviving prisoners – and prison guards and administrators – to try and provide a record to explain the reasons why people agreed to help operate these prison camps. At the core of much of humanities research is recording the memory of human experience, while at the same time we analyze the way we construct out memory. Why do we see certain acts as positive and ethical in one context, yet immoral and unethical in other? We, indeed, actively engage in deconstructing social myths, but in critically sound manner. Understanding the core of the foundations of our theology and ideology allows us to understand how better to engage with our current surroundings at all levels: interpersonal, ideological and ecological.

Displacing ourselves from our regular environments to find materials not readily available in our home institutions is the most important aspect of our summer estrangement. Many researchers take a few weeks to visit libraries such as the Library of Congress, or archives that contain primary materials for their research. At the same time, we as researchers can take time to place our materials within a greater historical and cultural context.

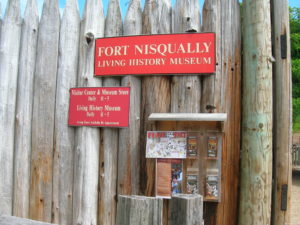

Sometimes, exposure to different places can also allow the researcher to think in a different way about their topic. Among the places I have visited this summer, the two that have struck my analytical mind the most was my visit to George Washington’s winter headquarters in New Jersey and Fort Nisqually in Tacoma, Washington. In both cases, the original pretext for the visit were completely touristic. The visits provided me with the opportunity to visit some examples of pre-modern architecture. In the case of Washington’s headquarters, the eighteenth century domestic architecture proved surprisingly flexible to the needs of the young nation’s military leadership. In these early years of the twenty-first century, one would be hard pressed to imagine a regular home suiting the needs of a large detachment of military officers, particularly officers as high ranking as Washington and his officers.

The visit to George Washington’s headquarters was juxtaposed with a visit shortly thereafter to the John Deere Pavillion in Moline, Illinois. It is meant to be a hands-off tourist attraction to feature John Deere’s amazing technology. It actually also makes it possible to envision the changes in the definitions of rural agricultural culture since World War II. The tractor below runs around a quarter of a million dollars, and is used to farm thousands of acres at once.

Between New Jersey and the Pacific Northwest, there was the Midwest trip, with the trip to the John Deere Pavillion, an excellent hands on museum of agricultural technology..

In the case of Fort Nisqually, one gets to realize how labor intensive life even during the middle of the nineteenth century was. The visit to Fort Nisqually contrasted nicely to the presence of the Washington state ferries, which many Tacoma and Seattle residents take for granted but which produces a sense of awe even among those who used to live in King County in a former life. The juxtaposition of mid-twentieth century technology with the reconstruction of life from the bare beginning of the modern era, combined with the post-modern transformation of downtown Seattle all came together to create this visual narrative of the nature of modernity and change in the last century.

The visit to Fort Nisqually impressed even more because it exists in the middle of the most developed area of Washington state, King and Pierce counties.

The visit to Fort Nisqually impressed even more because it exists in the middle of the most developed area of Washington state, King and Pierce counties.

The opportunity to view such contrasts in such a short period of time, and to feel the drastic contrasts in a three dimensional manner, allow one to better understand descriptive moments in literature. It also allows one to identify great literature. Great literature allows one to feel the structure without being there, brings out the stony without having to travel three thousand miles. Understanding how a stone – or in this case, a ferry or a really big piece of seaweed – can allow the reader to get over the initial stage of unbelief.

What truly struck the greatest visual chord was the area surrounding the Saint Benedict Dominican Retreat Center in Mackenzie Bridge, Oregon. The area was surrounded by a huge national park. It is also possible to walk to deposits of volcanic rock not too far from the center.

The chapel.. The interior is made with local wood, giving a new meaning to the term “locally sourced…”

As Shklovskii noted: “If we start to examine the general laws of perception, we see that as perception becomes habitual, it becomes automatic. Thus, for example, all of our habits retreat into the area of the unconsciously automatic; if one remembers the sensations of holding a pen or of speaking in a foreign language for the first time and compares that with his feeling at performing the action for the ten thousandth time, he will agree with us…” Separating ourselves from our normal surroundings becomes critical to developing new ways to contextualize our normal surroundings, to explaining what is it that allows our everyday surroundings to become “automatic.”